There’s No Place Like Home

November 10, 2018

When I was five years old commercials about companies helping you track your lineage began popping up on my family’s TV screen. It was exciting to think that maybe I was not only Nigerian, but possibly Cameroonian, or Ghanaian, or maybe something a little more far fetched, like Ethiopian. Sitting at the computer screen, typing every variation of my father’s last name it was clear that those advertisements were never really meant for people like me.

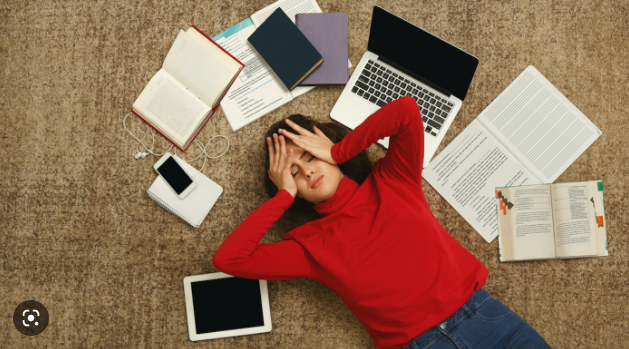

This experience helped me realize that there exists a difference you can’t see, a difference that simply lurks in the back of your mind, and surfaces only in certain situations. Though there are many ways to define people when it comes to lineage, one group seemingly has no single place in the world: “second generation Americans” especially those who struggle to fuse two completely different cultures from two completely different places. To make matters worse, these people can never fully embrace either culture.

Clashing cultures takes a toll on a person’s sense of self. There are no sleepovers, first dates, family dinners or any usual American traditions in my house. These types of actions are marked “evil” originating from taboo practices, or just simply are not done where my parents are from. Seeing the “perfect American family” archetype and knowing you don’t fit it hurts so much that it makes you wish you could change. This crosses borders as well because here listening to African music and eating Jollof rice is second nature to me, but in Nigeria, I feel like a complete stranger. A country’s culture is more than just its music and food. It’s hard to assimilate when you don’t get the jokes, can’t mimic the lingo, and overall feel like an outsider looking in. Second generation children can’t fully identify as American, but don’t fit in anywhere else either.

Aside from internal conflicts, we are often rejected by groups we should seemingly identify with. In particular, the discord between African-Americans and Black-Americans persists though no one wants to admit it. A group of marginalized individuals chooses to consume itself rather than unify and fight for a common cause. Genetically, we are the same, despite specks of Native American and Caucasian in some Black-Americans’ ancestry. Today, we’re born in the same hospitals, go to the same schools, and wear the same clothes as Black-Americans among other things. So why is there so much of a need to separate ourselves and demonize each other? The answer lies in our yearning to belong. African-Americans and Black-Americans alike believe that if we can make ourselves more desirable, we can receive the admiration of those who truly own this country: rich, white people.

The only way to, at least partially, get past the alienation that second generation Americans face is to hide our heritage, shorten our names so our friends can pronounce them, deny any evidence of an ancestral background, and allow others to mock us every chance they get. Then, maybe we’ll be real Americans. In reality, there’s nothing that rids us of our culture, nothing that makes us completely fit into American society. In this way, second generation Americans are left in a limbo, constantly floating between two lives.