Washington’s Mind Game

The Good Side of American Political War

May 28, 2019

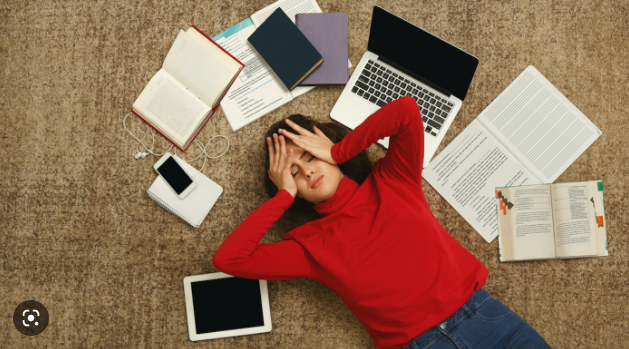

In contemporary politics, every action undertaken by a politician, committee, or government body is heavily calculated. Every media appearance is staged and scripted as if it were a movie, and a vote on a bill seems to be more partisan than it is ideological or dutiful. Every “yay” or “nay” from Congress that used to represent the people’s thoughts or be seen as “in the best interest of the country” now seems to be lost in the face of political meanings.

Take the Senate’s choice to vote on the Green New Deal in March, for instance. Although the public is uncertain of the motive behind Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s choice to push a Senate vote on the legislation, many Democrats, including Senator Ed Markey, who introduced the legislation in the Senate, view it as a partisan move. “By rushing a vote on the #GreenNewDeal resolution, Republicans want to avoid a national debate & kill our efforts to organize,” Senator Markey tweeted following the vote.

In protest of the rushed vote, Senate Democrats, with two exceptions, voted “present” on the legislation. A vote of “present” means that a representative or senator refuses to take sides on a bill. The Democrats’ rationale in casting such a vote was that, since the Republican Party holds control of the Senate, passage of the legislation seemed unlikely regardless of how Democrats chose to vote. Hence, voting “present” would demonstrate the Democrats’ resistance to the vote better than a seemingly-futile “yes” vote.

However, it is notable that many Democrats have been skeptical of the Green New Deal, including Senators Joe Manchin and Dick Durbin, who called it a “dream” and an “aspiration.” By voting “present” on the bill, they could disguise their reluctance as party loyalty in a way that their constituents, many of whom are supportive of the Green New Deal, would not be able to criticize them for going against constituents’ wishes.

Yet, not every aspect of this political war is negative. Political motivations can be a significant factor in ensuring that the three branches of government are kept in check. For instance, from November 2017 to September 2018, Democrats on the Oversight Committee of the House of Representatives have requested and been denied sixty-four subpoena motions “to help us gather the facts about the crisis of corruption in the Trump Administration,” then-ranking member Elijah Cummings said.

Under the leadership of Republican Chairman Trey Gowdy, who assumed his role during that time period, the House Oversight Committee had only issued one subpoena to the executive branch, compared to the fourteen subpoenas Representative Gowdy issued as Chairman of the Benghazi Committee under the Obama administration.

After Democrats gained control of the House in the 2018 midterm election, a lot more tension was evident between the chamber and the White House. Most notably among them is perhaps the House Judiciary motion to issue subpoenas for Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report in which he details his findings regarding the Russian government’s involvement in the 2016 presidential election.

Although some Republican members previously claimed to support the release of the Mueller report, seventeen on the Judiciary Committee voted against issuing the subpoena when the opportunity to prove themselves accountable arrived.

This is, by no means, to say that political division is a good thing. Regardless of whether it increases transparency in government, political division creates the potential for gridlock in policymaking and doubt surrounding elected officials. It has become increasingly difficult to determine whether officials’ actions are carried out in the best interest of their constituents or as a political weapon. But politicians are not the only individuals responsible for what politics have become. It can also be attributed to Americans’ political behaviors, the evolution of party systems, and the light that the media has painted government officials in.