The Tipping Point

Has standardized testing gone too far?

April 21, 2015

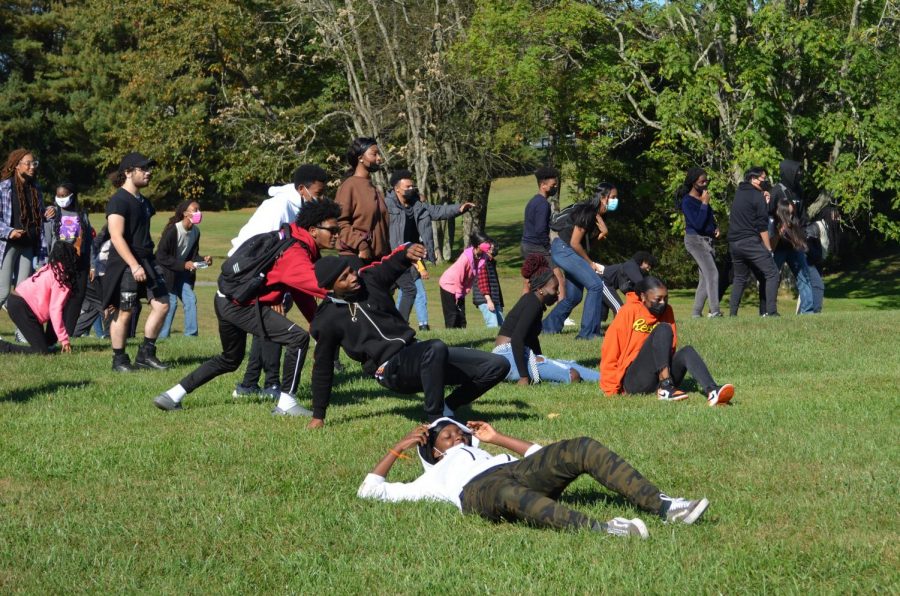

Have you noticed the increase in standardized testing within the last few years? If you are a public school student, you sure have.

With the HSAs, SAT/ACTs, MSAs, and now PARCC assessments that students in grade levels three to twelve take, the number of government-mandated tests has climbed to an all-time high. Teachers and students alike are equally affected by this increase in high-stakes testing.

However, the issue lies not with the pros and cons of frequent testing, but rather with the increased role that standardized tests have taken in American education. These tests certainly have their place, but testing multiple times a year is out of line.

Standardized tests can be found in American schools as far back as 1926 when the SAT was first administered to students. The ACT followed in 1959, and the HSAs were established after the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. When President Bush passed the No Child Left Behind Act, he felt American students were suffering from low literacy rates and overall education deficiency. For example, in 1998, 60 percent of 12th-graders were reading below proficiency according to the US Department of Education. As a result of the low test scores, these “fill in the bubble” tests, although not mandated by the government, necessary if states wanted to earn “Race to the Top” funding, which gave school districts money to improve the educational resources available for teachers and students. Some might see tracking student test scores as a negative aspect of testing because it appears that the government gives more money to the smarter, richer school districts, which often perform significantly better than poorer districts, which are left to fix their own problems. Opponents of standardized testing fail to understand that tracking student progress can benefit students because if the government can see that some school districts are lagging behind, they can find out which schools need more funding for learning resources. Although this is already happening, many parents and educators are oblivious to the true intentions of the government and the true intentions of standardized testing in schools.

Others argue that standardized testing encourages teachers to “teach to the test,” which results in students focusing on memorizing material instead of learning it. Poor test scores can affect a teacher’s reputation, and now there has been talk about establishing a correlation between student test scores and teacher salaries through a concept known as “value added.”

In Valerie Strauss’ article “The Fundamental Flaws of ‘Value Added’ Teacher Evaluation’,” she states, “The stakes are high because teachers could lose their jobs if they have low ratings on these new evaluations. Their salaries and promotions could also be affected, as well as their standing among their peers. Higher test scores mean higher salaries for teachers.” Relationships between teacher salaries and test scores may motivate teachers, but it also gives them incentives to cheat. In Freakonomics by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt, they argue that at its core, economics is the study of incentives. They provide an example of standardized testing in relation to the concept of “value added.” In two sixth-grade Chicago classrooms, the student-test answer patterns were analyzed by school officials and they discovered that in one classroom, distinct patterns could be seen in most answer sheets. The teacher not only filled in the correct answers, but also filled in the incorrect answers on a few tests as a way to ensure that no one would detect the tampered answers. Overall, Dubner and Levitt report, officials found that “Chicago Public Schools data reveals evidence of teacher cheating in more than two hundred classrooms per year, roughly 5 percent of the total.” These teachers cheated because they wanted a higher salary or simply because they wanted to protect themselves from the power of the school system and the federal government. Although most teachers would not cheat to achieve these benefits, it is human nature that a small percentage of teachers will be dishonest just to gain potential benefits.

Student test scores should reflect the student first and the teacher second. Although scores can be a tell-tale sign of an insufficient teaching style, it is ultimately the student’s responsibility to take full advantage of all resources provided in school and to get the best education possible.

In Chad Aldeman’s article for the New York Times, “In Defense of Annual School Testing,” he quotes former President Bill Clinton’s thoughts on standardized testing. President Clinton, in the fall of 2014, said, “I think doing one in elementary school, one at the end of middle school and one before the end of high school is quite enough.” Clinton’s proposal is a happy medium between testing every year and eliminating testing all together. Standardized testing is a necessary tool for both the government and educators to not only monitor American student progress but also teacher success and collective school district progress.