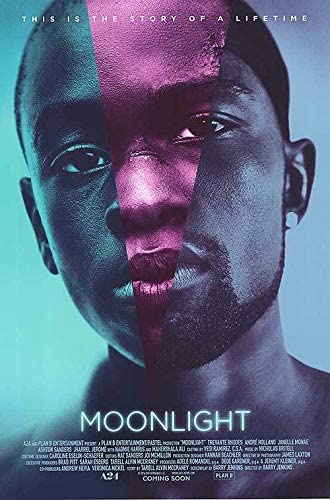

Moonlight and The Importance of LGBTQ Representation

Moonlight won the 2016 Academy Award for Best Picture as well as several other awards.

April 16, 2020

When Moonlight won Best Picture at the 89th Academy Awards, it’s historically significant victory was overshadowed by the confusion surrounding the announcement. The wrong film was announced at first, which unfortunately had many focused on the gaffe rather than the cultural and political importance of the winning film.

This coming-of-age film is based on Tarell Alvin McCraney’s semi-autobiographical play, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, and was adapted to film by director Barry Jenkins. It follows Chiron, a black, gay man raised in poverty, throughout three crucial periods of his life spanning from childhood to adolescence to adulthood. The structure of the film highlights the idea that, just like race and socioeconomic status, someone’s perceived sexual orientation affects how society treats them, and heavily influences who they become in adulthood. Chiron’s queerness, and the inherent isolation that tends to accompany it, is crucial to his development. Along with its emotionally impactful story, the film is technically masterful — from James Laxton’s cinematography to Nicholas Britell’s musical composition to Mahershala Ali’s outstanding acting — and its beauty is only magnified by the fact that, unlike many similar films of past years, Moonlight doesn’t end in tragedy.

Decades ago, we couldn’t have seen LGBTQ representation as genuine as this, not only because of the lack of queer filmmakers in Hollywood, but also because of the culture of blatant homophobia present in the industry since the introduction of the Hays Code in the 1930s. This set of regulations, influenced by the Catholic church’s control over the industry at the time, censored the depiction of subjects deemed “immoral” or “sexually perverse” and it was widely understood that homosexuality was therefore prohibited. Some mid-20th century movies did feature gay characters, but they were obligated by this code to present them as villains or deserving of a tragic ending. They couldn’t show audiences that this “lifestyle” was at all acceptable. The Hays Code dissolved in the 1960s, and while this meant that movies could once again depict drug use, glorify crime, and have sexually suggestive scenes without getting censored, the lack of positive LGBTQ representation persisted.

Even a decade ago, back in 2009, according to a GLAAD (an organization dedicated to monitoring LGBTQ portrayal in media) report, only 3% of series regulars on network TV shows were LGBTQ. Television has made great strides since then both in quantity and quality of representation, with the aforementioned percentage increasing to nearly 9% in 2018. However, film still hasn’t caught up. Out of the 109 movies released by the seven largest movie studios in 2017, only 12.8% even included LGBTQ characters, let alone focused on them.

It’s no wonder, then, why Moonlight’s Best Picture win was so groundbreaking at the time. Several LGBTQ films — Milk, Brokeback Mountain, and Carol — had been nominated for big categories in the past, but none of them had ever claimed the ultimate prize. Best Picture is one of the highest honors a movie can receive — among it are classics like The Sound of Music, The Godfather, Rocky, and Titanic. This award puts Moonlight in an indisputable position among the most important movies of the modern-day. Giving this honor to a film representing a marginalized perspective highlights that these stories are valuable and valid.