How the Music Industry Disrespects Black Artists

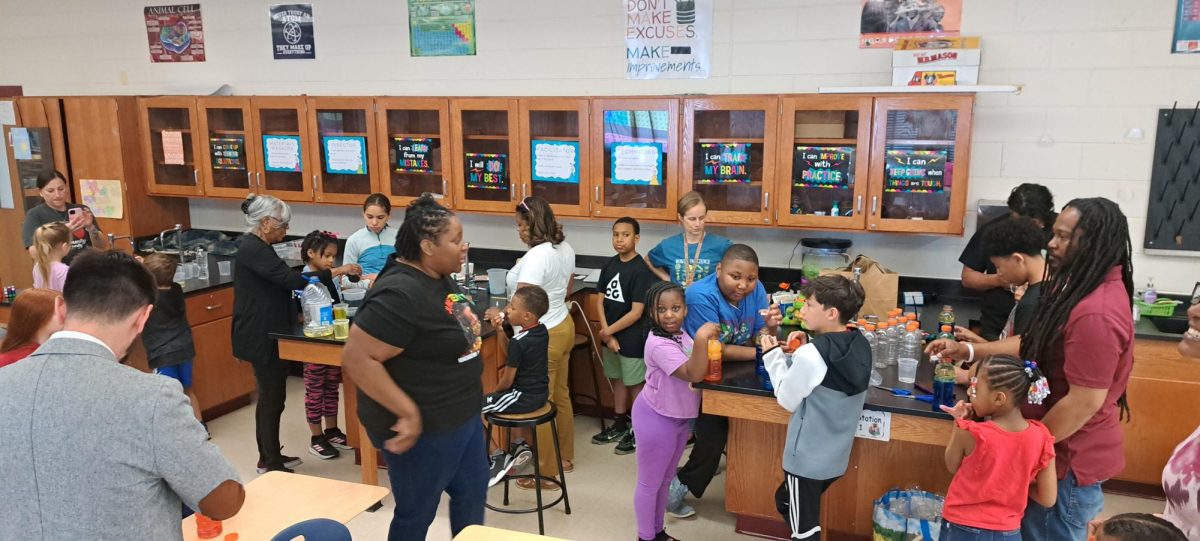

Beyonce poses backstage in 2017 with her two Grammy awards.

December 8, 2020

Do you remember the 59th Grammys in 2017?

Let me refresh your memory. This was an iconic night when the vocal powerhouse Adele literally broke her Grammy Award trophy for Album Of The Year. She won for the critically acclaimed album “25,” and was gushing and going on about how Beyonce deserved AOTY that night for her groundbreaking project “Lemonade.”

Beyonce’s consolation prize? Best Urban Contemporary Album.

Just one year earlier, at the 58th Grammys in 2016, Taylor Swift won Album of the Year – for the second time in her career – over Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper Kendrick Lamar.

Lamar’s consolation prize: Best Rap Album.

Both of these instances created a firestorm of controversy and forced people to address the question of why mostly white artists win or are recognized in major categories like Album Of The Year (AOTY), Record Of The Year (ROTY), Song Of The Year (SOTY), and Best New Artist.

While the 61st Grammys in 2019 awarded Childish Gambino Record of The Year for his single “This Is America,” the award show backtracked the next year. The biggest artist in 2019 was Lil Nas X, a black and gay artist. According to Billboard, his viral hit song “Old Town Road,” featuring country singer Billy Ray Cyrus, peaked at #1 on the Hot 100 charts and stayed there for 45 weeks making it the longest number one in Billboard history.

Yet, he didn’t win any major categories at the 62nd Grammys in 2020, although he had been nominated for several. Instead, it was the young pop artist Billie Eilish who swept all the categories winning AOTY, ROTY, SOTY, and Best New Artist, even though Lil Nas was nominated for all except SOTY.

Writer and media scholar John Vilanova commented on the issue saying, “This is what systemic racism looks like.” Vilanova notes that the music industry has a reinforced bias towards Black artists that is rooted in a “coded racial superiority in high/low culture hierarchies and musical genres and styles.” The Grammys is supposed to determine the merit of music and acknowledge the excellence of artists. But when Black artists aren’t recognized, it makes it seems like we are not good enough. It’s very common over the years where the industry and the academy overlook the musical accomplishments of Black people; even legendary work like Michael Jackson’s “Off The Wall” or Prince’s “1999” were never nominated. It’s not just a coincidence, it’s racism. Black culture has always been influential in pop culture, especially in music. It was Black people who created and started the genres like hip-hop, R&B, house music, jazz, and rock. The music industry wouldn’t be where it is today without Black artists and executives, yet they aren’t respected.

Questions on how Black artists fit into the music industry eventually sparked criticism with the word “urban” and other genre criteria when it comes to a Black artist. The 28-year-old musician Tyler, The Creator, during his acceptance speech after winning Rap Album Of The Year at the 62nd Grammys in 2020, candidly spoke up about how he feels. He stated that the Academy often puts Black artists in urban or rap categories as a “backhanded compliment.”

“It sucks that whenever we — and I mean guys that look like me — do anything that’s genre-bending or that’s anything they always put it in a rap or urban category. I don’t like that ‘urban’ word — it’s just a politically correct way to say the n-word to me,” Tyler said.

Tyler’s words were met with, surprisingly, respect and acknowledgment. His speech reached social media and much news coverage. Tyler isn’t the first to address the Grammy’s racial bias. Frank Ocean and Kanye West boycotted the award show prior. In fact, Tyler’s comments started a much-needed conversation.

The truth is, Tyler is right. The word “urban” is often used as a substitute for racial stereotypes. People associate the word with Black culture, our outfits, our homes, and our music. “Urban” has become a “catchall” word to categorize all Black artists and Black radio,

Some may argue urban categories “were built to give Black executives a true voice and an opportunity to run and manage an aspect of the business that was largely being ignored by the corporations,” the head of urban promotion at Columbia Records, Azim Rashid, writes on Instagram. However, urban categories ultimately divide Black artists and executives from better opportunities like exposure and money.

At the same time, white pop artists are allowed to explore multiple genres and take sounds from R&B and Hip-Hop while doing well on mainstream media. Take for example the Macklemore’s hit song “Thrift Shop” (2012), Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings” (2019), or even white rapper Eminem’s whole career, all having major hip-hop elements and huge mainstream success. But when an artist of color does it, “The industry will still pigeonhole, saying, ‘Oh, this has to go to urban,’” says the R&B artist Jhene Aiko.

Recently, with the uproar of criticism and the emergence of Black activism in the wake of George Floyd’s death, the music industry has tried to display ways of supporting the Black community. On June 2, the industry took a day of reflection using the campaign #BlackoutTuesday created by two Black women who work in music, Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang.

Major record companies and popular streaming platforms pledged an abundance of donations to the campaign. Warner Music Group and Republic Records, as well as large broadcasting radio companies like iHeartMedia promised to not use the word “urban” anymore and instead will refer to genres as Hip-Hip, rap and R&B. The Grammys also announced that they will be renaming their “urban contemporary category” to “progressive R&B.”

Unfortunately, I’m afraid that these performative promises will be broken and are not effective. It’s great that the industry is finally acknowledging their institutionalized racism, but these token acts and donations won’t necessarily fix the racial issues. Not using the word “urban” isn’t enough. Donating money isn’t enough. The problem is in the systemic racism that’s been ignoring and suppressing great Black art. And with the recent announcement of nominations for the 2021 Grammys, it sadly shows how much work needs to be done to fix the racist system.

Pecola Breedlove • Jan 21, 2021 at 3:20 PM

I can hear your voice loud and clear! It would be nice to see a follow-up that discusses the representation of Blacks within the music industry- especially the A&S level.