BIPOC Representation in History Matters

December 11, 2020

History is a story, an interwoven map of trillions of threads that traverse time and people. I would argue that there are probably even more stories than that – narratives that never make it to the textbooks or media faces. These threads loom over us as skyscrapers and stretch under our feet in between the concrete.

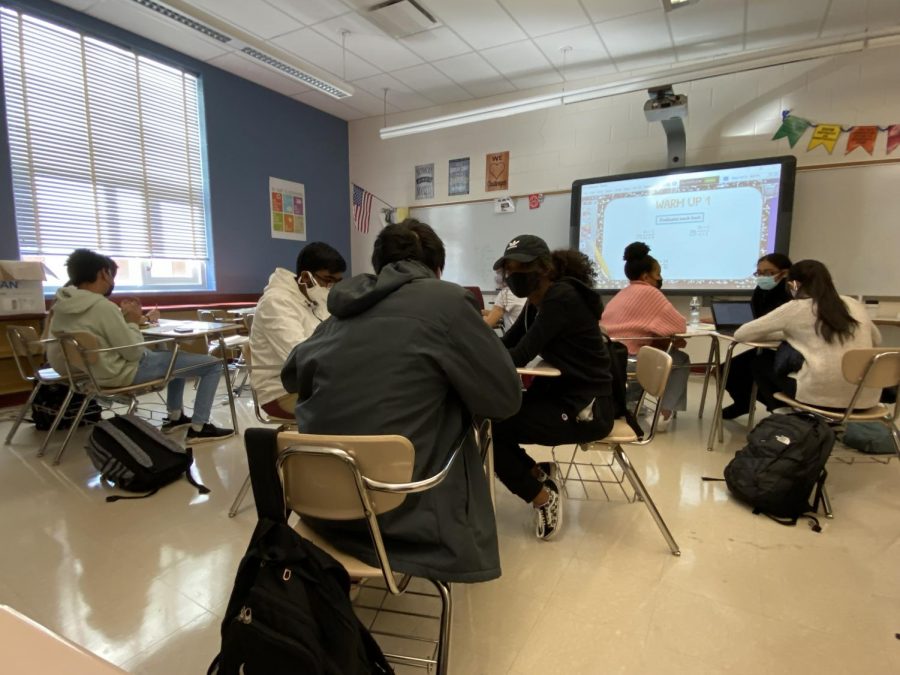

History is important to understand how the world is, how it got this way, and what it will become. With the returned global attention on marginalized communities, it would be fair to bring up their limited place in history classrooms.

For years – especially over the last decade, or so – there has been more focus placed on establishing African American history classes in public schools. This has promoted broader awareness and understanding of not only that community’s struggles, but also of their achievements that go beyond the scope of the American story.

Although there has been progress in embracing a more diverse and inclusive history of African Americans in the U.S., more work is necessary to shine light on stories of the black community and the breadth of their achievements. And while the inclusion of these stories is more prominent in curriculums, and individual classes on African American history are added to course catalogs in more primary and secondary schools, there are still other communities whose stories wane in the shadows, forced to the back of our nation’s history and often forgotten or ignored.

I remember looking at my U.S. History textbook back in ninth grade and wondering about the sizes of the sections devoted to certain groups during the twentieth century’s civil rights movement. I saw the names of my community’s leaders, names that are as familiar and a part of me as the alphabet, but it was the first time I had seen the names of Cesar Chavez and Dennis Banks. Even then, they were restricted to just a few pages, maybe less. I can’t even remember if they covered more than three pages.

History is a tricky subject. There are intersections and juxtapositions in the whole field of study. Such as in the Vietnam War, there were Native American, Asian American, and Hispanic soldiers who fought alongside African Americans soldiers and their white counterparts. Their stories all intersect in this historic event as they share in the experiences of war and differ in their realities at home in America. In history, some details are uncertain while others have been proven through archaeological findings, government documents, and extensive research. However, it wouldn’t hurt to have more spaces devoted to all people of color in our textbooks.

This request isn’t new. This issue has been going on since before I was born. Marginalized communities have been asking for the opportunity to be heard, to have a voice, to see themselves reflected in all parts of society, including in schools’ curriculums and textbooks. Each year that people of color were ignored and denied, they continued to speak and advocate for inclusivity. Our schools’ instructional materials and curriculums should be a reflection of those voices and all those efforts, past and present.

Schools are one of the primary places where people receive information. Usually, what is taught in school about American history is considered fundamental to what should be remembered about the nation and how things came to be. Overall, American history classes should devote more time to speaking about the full stories of people of color in America. Better yet, every school should create whole classes for these areas of history so as to provide a full curriculum that gives students the chance to dive more deeply into the histories of groups long pushed aside or brushed under the rug.

Perhaps this is an article attempting to bridge those gaps between the BIPOC community and their representation in history. Perhaps it is an article trying to encourage a fundamental understanding of other groups in this country and their histories that don’t just include pain and blood. Whatever it is, we need history in order to better inform our decisions for a united country and to understand the people who, after so long, have asked for a seat at the table. History provides one of those seats at the table.

Ydediya Hailu, grade 9 • Jan 13, 2021 at 11:11 AM

great work and great dialogue and article.