The Dark Side of the K-Pop Industry

February 19, 2020

Korean pop music, or K-pop for short, has quickly become one of the most successful music genres in the world. Once confined to Asia, the now $15 billion dollar industry has gained popularity internationally, including here in the United States.

Last year, 2019, was an impressive year for the genre which had artists breaking numerous records and gaining a cult-like following. BTS, one of the most widely known groups, has consistently appeared on Billboard’s Hot 100 and amassed 78 million views on one of their music videos in just 24 hours, breaking the YouTube record. It’s not hard to see the group’s appeal. The synchronized choreography, catchy melodies, high production values, and the attractiveness of the group’s members are no doubt the source of their growing popularity. But behind the impressive performances lies a cutthroat industry that allegedly exploits its artists through what many call “slave contracts” and controls their personal lives to a degree unseen in the West since the mid-20th century.

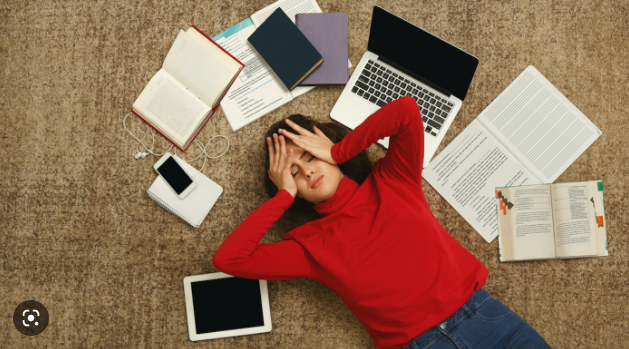

Fame is no small thing in Korea; those who want to be K-pop stars — known as “idols” — train for years, sometimes starting as early as 11, and the majority of them never become commercially successful. It’s a fiercely competitive system and once someone is “discovered,” they still aren’t assured success unless they sign with one of three labels that currently dominate the industry, SM, JYP, and YG.

It’s an open secret within the industry that idols’ weight and looks are heavily scrutinized by their agencies throughout training and afterwards. These hopefuls are encouraged by label executives and trainers to get plastic surgery and some are put on strict dieting regiments at young ages according to pop-culture expert Lee Jong-im, in an interview with Yim Hyun-Su of The Korea Herald. Lee is also the author of Idol Trainees’ Sweat and Tears, a book that looks into what she refers to as the “factory-like” conditions of K-pop the training system.

Even when they do find success, idols face daunting expectations. If idols aren’t constantly living up to the expected standards, they are heavily criticized by their labels, the media, and the socially conservative Korean public. In terms of dealing with this constant criticism and expectations of perfection, they are hardly given sufficient access to mental health services. Late last year, two female K-pop idols, Goo Hara and Choi Jin-Ri committed suicide in their homes; Both had suffered through extensive cyber bullying throughout their careers, Choi for openly supporting feminism, and Goo for explicit photos of her that had been leaked online. Some fans online suggest that the agencies are to blame for not looking out for the well-beng of their artists, others suggest that it’s because depression is taboo in South Korea, which discourages idols like Goo and Choi from seeking help.

Many members of K-pop groups don’t speak openly against the issues within their industry, so it’s difficult to get a complete picture of the struggles they face, but occasionally one will forsake their contracts to speak out.

In 2014, the leader of the group ZE:A, Moon Junyoung, went on a now-deleted Twitter rant directed at the CEO of Star Empire, the management agency in charge of his group. In it, he made a series of accusations, claiming unfair treatment and physical abuse, among other things. “From spot baldness to depression, I’ve suffered so much” he writes, adding that at one point, he was driven to attempt suicide. Many of the tweets were complaints about the artists’ treatment as well as a strict contract which he believed left him and his band members grossly underpaid and kept them under Star Empire’s control for over a decade. The situation has since been resolved, and Star Empire responded to the accusations, stating that they should have “been more attentive” to the feelings of their artists and that they would work more closely with them in the future. After it was resolved, Moon went back on Twitter to add that what happened with him and his group is happening throughout the industry and encouraged the media and other CEOs to take notice and change their ways.

Though there have been notable improvements in recent decades, many K-pop idols still sign what are known by the public and the idols themselves as “slave contracts.” Multiple members from successful K-pop groups like EXO and TVXQ have recently filed lawsuits against SM, one of the biggest management companies in the industry, for restricting them under such contracts. Both allege unfair profit distribution and extreme contract periods. According to Han Sang-hee of The Korea Times, “this type of contract is standard in Korea’s entertainment industry.”

The contracts, the restrictions, and the amount of control K-pop executives have over their artists is reminiscent of the “Star System” that plagued 1940s Hollywood. Movie studios selected promising young actors and made them into stars via multi-year and multi-film contracts. These actors often had to deal with abuse and signed morality clauses that determined how they acted in public, all in order to hopefully become ‘rich and famous’. This system fell apart when the stars themselves started taking legal action. They found that being free agents was more beneficial to them and their careers, and eventually independence became the norm. Korean idols have started to follow a similar course, but only time will tell if the socially conservative environment of South Korea will be as accepting of this kind of individualism.